This discussion will take an initial look at the extremely active winter storm season of 2023/2024. An enduring presence during the storms, Total Water Level (TWL) will be considered, alongside erosion common to both Sand and Shingle beaches in East Anglia.

Given the complex nature of the winter storms it might be simplistic to just identify one element, Total Water Level (TWL), when additional destabilising elements such as Wind Speed and atmospheric pressure also play a major role. But TWL can also play a major part, in agitated, elevated sea levels, extreme rainfall and extensive flooding of land and properties.

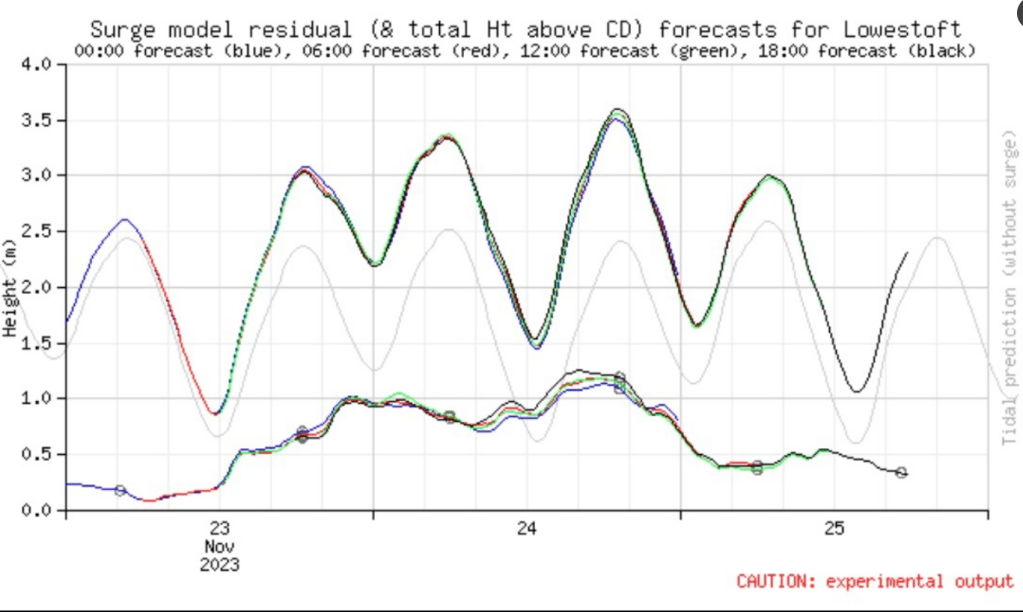

Winter Storms season of 2023 2024, begin with Storm Babet, the second named storm of 2023 on Friday 13th October, it continued through Monday 16th October until Friday 20th October. Storm Ciaran followed 9 days later on Sunday 29th and continued until November 4th. A considerable storm surge of over 1 metre occurred on Friday 24th November with a larger storm surge of just under 2 metres on Thursday 21st and Friday 22nd December 2023.

In 2024 on January 14th/15th, a Storm Surge measuring just under 1 metre hit the East Anglian coast. On 22nd January, Storm Isha and then Storm Jocelyn occurred in quick succession with 3 storm surges occurring in a week, the largest on Wednesday 24th January, measuring over 1 metre. On 30th January/February 1st, Storm Ingunn hit Norway, generating a Surge of over 1 metre. On Sunday 25th and Monday 26th February a storm, localised mainly in the Southern North Sea saw a 0.5 metre surge recorded for Lowestoft, with a surge of nearly a metre measured at Sheerness. Finally, on the evening of February 29th/March 1st stormy conditions generated a surge of around 1 metre at Lowestoft.

Additionally, particularly High Spring Tides in March 2024, coupled with exceptionally high rainfall and strong winds, caused considerable erosion and flooding in places.

The list of storms above is a summary of a very intense period of activity. Therefore, this discussion will assess whether the TWL approach, can enable an assessment of the impact of storms on erosion of cliffs, dunes and beaches.

It is thought that in storms where TWL exceeds 3.9 m water levels can reach the dune or cliff toe, potentially causing hollowing of frontages and lowering of beach surfaces. Methods to assess TWL often use measures of Significant Wave Heights (SWH) that reach or exceed Storm Alert Thresholds. As it is thought that such thresholds, can initiate movement of beach material. The table below lists the SWH for Happisburgh, Lowestoft and Felixstowe for winter storm season 2023/2024.

SWH heights hint at TWL at points on the coast where measures are taken, but they also give a picture of the variability of agitated sea states and how local they can be at times. For example, for November 24th, SWH of 3.6 metres is recorded for Happisburgh, above Storm Alert Threshold (STA), conditions that might contribute to the collapse of the road at nearby Hemsby. But SWH at Lowestoft remained below STA, close to where the road also collapsed at Pakefield.

However, it is interesting to consider how common erosion features appear on beaches, despite the sections of coast being comprised of different layers of sediment. Photos taken on 20th January at Thorpeness and on 16th February at Pakefield, could be said to show wave height reached when dune face scouring occurred and could suggest the TWL present on the beach.

The potential energy in the TWL present on beaches is suggested in the photo below, taken at Minsmere that shows old wartime sea defences that have been uncovered on a beach stripped of shingle, with signs of a Scarp or cliff appearing to form in the remaining Shingle on the Upper Beach.

Cliff-like Scarps on Shingle beaches are said to only be maintained if physical conditions, enable sand to infill spaces in between the Shingle, to sustain the steep feature. Waves can cut into the bottom of Scarps, which can also influence subsequent wave direction. Increasing transportation of sediment off-shore.

Another significant type of erosion that has occurred at several coastal locations in East Anglia is Cliff failure, due to rainfall. Instances of this erosion have been observed at Dunwich and Pakefield in Suffolk and Overstrand and Sidestrand in Norfolk. It has been found that in stormy weather it is the combination of TWL reaching the Cliff toe and high rainfall that can cause cliff collapse, but it is thought that heavy rainfall is the predominant cause of cliff collapse in East Anglia and other coastlines around Britain. Particularly as at Dunwich, it was said that foredune on the beach had accreted sediment, so waves were not hitting the toe of the cliff.

The two charts below from the Met Office show rainfall levels for January and February 2024.

In January there were around 75-125 mm of rainfall and in February East Anglia had its wettest February on record, with 106.4 mm of rainfall.

Rainfall can cause severe damage to cliff structures in the following ways. Referred to as a Terrestrial process, rainfall can affect elements that determine the volatility of cliff materials. On the beaches of Thorpeness and Pakefield, with cliffs partly comprised of Glacial Till and sands, two views on the impact of rainfall on these surfaces are suggested.

For Moderately cemented sands in cliffs that resist wave attack collapse can occur due to the penetration of rainfall soaking through materials. This process is aided by Desiccated Cracking causing sections of material to develop an imbalance that can lead to failure.

For Weakly cemented sands, wave action succeeds at eroding the cliff base with erosion and instability progressing up though the dune structure. As material falls from the cliff surface due to wave action, volatility develops in the upper cliff and these combined weaknesses cause collapse.

At a British Geological site at Overstrand in Norfolk a 300m section of cliff was studied located roughly halfway between Overstrand and Trimlingham. In this location, rainfall is thought to be main driver in cliff retreat, due to the abundant presence of clay in cliff materials. In this context, rainfall is thought to have the following impact on cliffs in this area.

There is thought to be a greater likelihood of the formation of pathways across cliff sections without vegetation, with subsequent movement of sediment through the gullies. This could enhance the formation of mudslides which can transport sediment down the cliff frontage. The level of the water table within the cliff can also be elevated, causing water to percolate through the frontage. Water resistant layers of cliff material can also funnel groundwater through the cliff. Breakdown of lumps of sediment across these resistant layers is thought to be caused by the materials progression across the plane of these channels.

Regarding these failure processes, in addition to heavy intense rain fall, it is also thought the cumulative impact of moderate rainfall can build up weaknesses. Such frailties can cause landslides days or months after initial rainfall episode. This makes it very important that members of the public do not walk close to the edge of cliffs and dunes as coastlines may have not recovered from the effects of heavy rainfall. A sign on the Dunwich coast warns walkers that path is still closed following cliff collapse weeks earlier.

In this discussion, consideration has been given to the severe storms that have hit the East Anglian coast in Winter 2023/2024. With a consideration of whether the concept of Total Water Level (TWL) can act as a contributory factor to types of erosion that occurred. TWL can be measured in Significant Wave Height, which can potentially increase likelihood of wave contact with the dune or cliff face. With some erosion features displaying the level of wave height that hit the cliff. TWL is also present as a feature in cliff failure due to rainfall.

However, in considering the usefulness of TWL in assessing the effects of winter storms, TWL can suggest volumes of water likely to have been in contact with dune and cliff faces. But it could be said there needs to be an additional element present, to move, agitate and initiate water volumes. Therefore, it might be better to consider TWL as one factor amoungst several destabilising tensions within complex storm systems that can erode and weaken fragile coastlines.