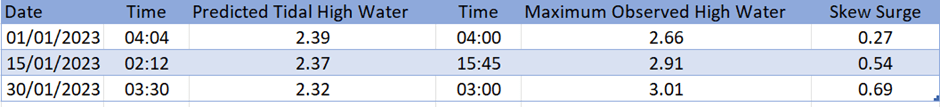

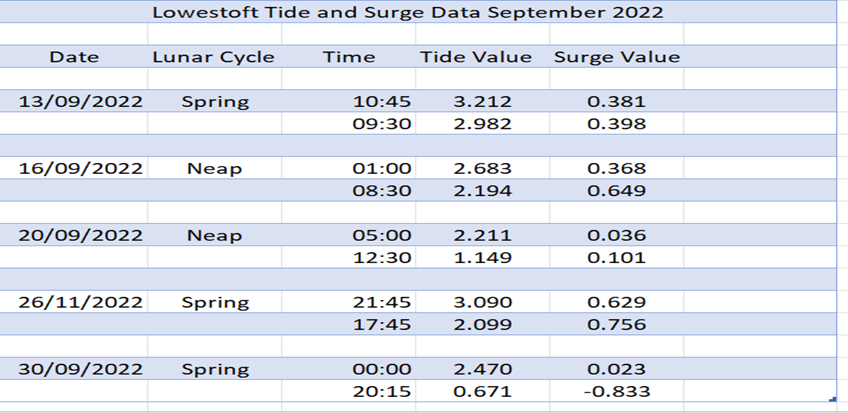

A recent discussion on alteredmarshes looked at a Skew Surge, the total difference between Maximum Predicted Tide Height and Maximum Observed High Water. It suggested the measure could aid storm analysis by suggesting specific conditions capable of generating a surge. However, information, such as the depth and size of a low-pressure system, whether the sea surface was still or agitated, wind speed and direction are needed to determine if a Skew surge, indicates the likely presence of severe storm.

This assertion was put to the test, on Friday 10th of March, when a low-pressure system stacked against the Suffolk and Norfolk Coastlines in the Southern North Sea, generated a storm surge that severely damaged a coastal resort called Hemsby near Great Yarmouth. A surge measure of nearly a metre in size was estimated at Lowestoft, down the coast and predicted tide heights at Hemsby were 2.9 metres and 3.4 metres.

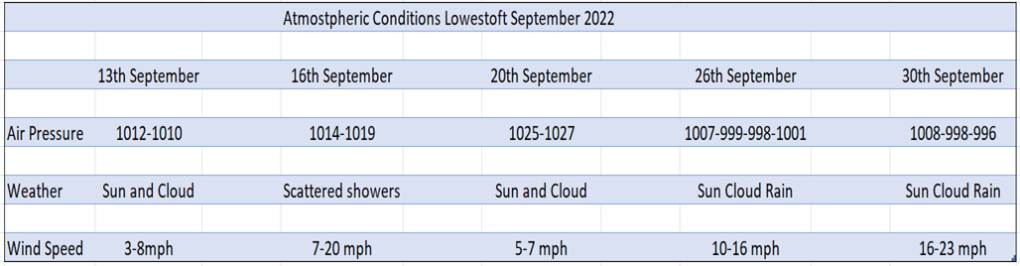

But to consider the significance of the storm surge on 10th March, it is useful to consider the likely presence of storm conditions around the time of the surge. Firstly, a low-pressure system, initially with tightly packed iso bars over Ireland, with low pressure values of 996-992 at 00:00 hours on Friday March 10th, was forecast to be situated over the North Sea and the Netherlands by 12:00 pm on Friday 10th March. Pressure systems can influence sea levels, with High Pressure causing a decrease in sea level and Low Pressure causing an increase. . It is said, a 1mb decrease in Low pressure can cause an increase in sea level of around 1cm.

Elevated, agitated sea levels can be sustained for extended period, due the effects of strong wind speeds transmitting energy to the sea surface making it taut and choppy. The larger the expanse of ocean subject to the wind, the higher the waves, their power amplified by the fetch – the expanse of the area of the ocean exposed to the wind. Wind speeds originating from the Northeast were recorded to be around 50 mph and Significant Wave Heights at Lowestoft were recorded as reaching 3:4 metres at times on 10th March.

Wave action on 24th February had already caused a large Scarp to be formed on the beach, this feature is defined as a steep slope formed by erosion, with the verb describing a process to wear or cut to form a steep slope. The Scarp is estimated to represent a 10 ft drop in beach material.

Conditions on the beach at Hemsby on the 10th of March were observed by Hemsby Independent Lifeboat crew and Hemsby Beach Café. They described the sea seeming to sound evil in the early hours of 10th March. Significant damage at Hemsby includes metres of cliff loss, which has resulted in residents undergoing the traumatic experience of seeing their home demolished. One resident reported around 17 ft of cliff material lost (just over 5 metres) in the space of a week. Videos of the storm surge on Friday taken by Hemsby Beach Café show waves seeming to eat away at the cliff frontage at Hemsby.

The erosive power of wave action is described quite well in the Observer Book of Sea and Shore. As well as the force of energy within a wave, pebbles can be propelled with force against the cliff surfaces, in addition to the corrosive action of sand against the cliff frontage.

Storm surges continue to bare their teeth, tearing chunks from the coastline of East Anglia, As data, forecasting and ferocious surges conditions on the ground further analysis of the surges reshaping and perhaps forever altering the coastline and perceptions of the North Sea.