As storms continue to batter the East Anglian coast, this discussion will consider marks left by storms Babet & Ciaran on two beaches in Suffolk and ask how useful it is to examine erosion through the lens of the Palimpsest. The term refers to how a surface or feature, when something new is added, continues to display residues of what was there before.

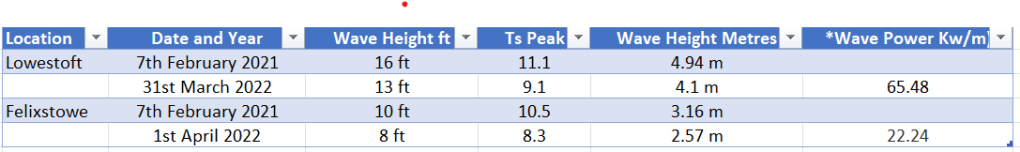

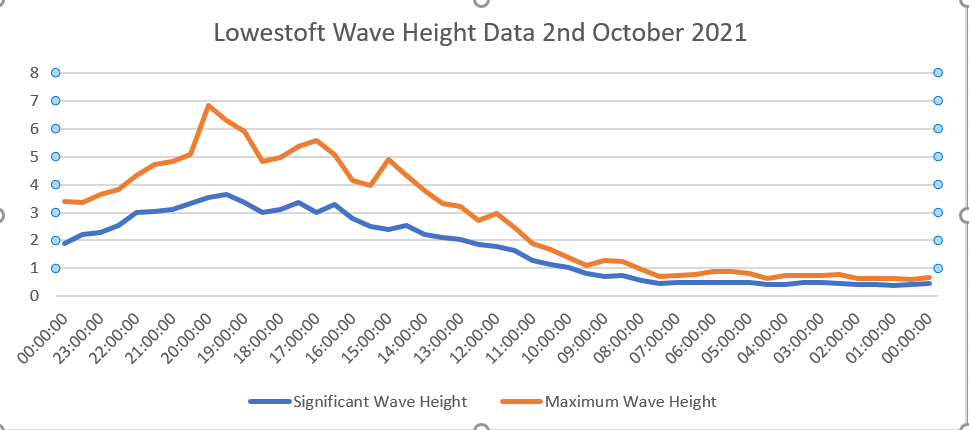

Firstly, data for Significant Wave Height (SWH) at Lowestoft recorded the highest values to date for 2023 during Storm Babet and Storm Ciaran. The SWH Storm Alert Threshold for Lowestoft is 3.11 metres. During Storm Babet, SWH was slightly below this and for Storm Ciaran it was noticeably above it.

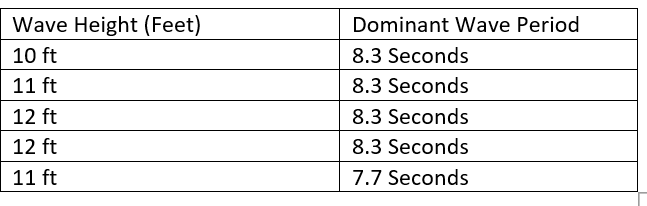

The Tpeak(s) or Dominant Wave Period, (DWP) is the period where the highest wave energy is centred. It is interesting that the DWP is the same for both wave heights. Particularly as the same DWP was also recorded for the highest SWH in 2022, during a storm on 31st March, when a SWH value of 4.10 metres was registered.

It is also worth noting that the highest value for Significant Wave Height was also recorded at Happisburgh, during Storm Babet on the 20th October. A SWH of 3 metres was registered, with a Dominant Wave Period of 6.2. The Storm Alert Threshold at Happisburgh is 2.74 metres.

Data for SWH has been considered because it enables an insight into the turbulence of the sea. It also provides the first noticeable signs of repetitions or noticeable exceptions. Patterns of wave behaviour that indicate continuity or require a new understanding, that learns from and develops, what has gone before. The first consideration of the usefulness of Palimpsest.

This term is discussed in a doctoral dissertation by Alison Stoneman, titled Holding The Line: contemporary poetry of British coastal change. PhD, Nottingham Trent University. Stoneman critically analyses Coastal Erosion poetry, and refers to storm damage on beaches, as sheets of features, that add to and alter marks left by storms before. Following storms Babet and Ciaran, erosion features of Thorpeness Beach and Sudbourne Beach in Suffolk were observed and will be considered through the lens of Palimpsest.

To start with Thorpeness, it might be quite straightforward to consider the framework of Palimpsest as a useful approach to analyse erosion at this location. As observations of erosion on the cliffs, show recent changes set in the context of the geology of the Pleistocene. Even though the beach changes quite dramatically, remnants of what has been laid down previously still show through. This is particularly relevant when considering the Pleistocene and the Palimpsest. As a couple of the poems analysed by Stoneman refer to Doggerland, a stretch of marshland that stretched between England and Europe, that was inundated by the sea at the end of the last ice age.

Observing current erosion through the lens of Palimpsest, is also useful as it enables a consideration of recent erosion and how this has affected the cliffs differently. Elevated wave action can scour the base and lower portion of cliff surfaces, stripping the surface and causing sediment to slump onto the beach.

At Thorpeness erosion of the cliff frontage, in the last 5 or 6 months has shifted further up the towards the Ness, at Thorpeness. The surface has been partially stripped of the vegetation and glacial til and fossilised remains and this has left bare sand which has been sculpted by wave action. However, the area of beach that has been spared recent erosion has been freshly eroded by Storms Babet and Ciaran. But because it had been stable for a few months prior to this, the glacial till/fossil sediment is still visible on the surface of the cliff and slumped sediment.

The next location, Sudbourne Beach provides a different setting in which to consider the Palimpsest. It is a high-energy shifting shingle beach, and in such a dynamic area, it is hard to identify threads of current and past coastal change. Recently, the ridge at the back of the beach has flattened with an extensive wide area of shingle showing signs of overtopping with shingle washed by waves into two tongues down to the marshes. The shingle fan stops short of the waterway behind the earthen flood defence that protects the River Alde.

On Sudbourne Beach, it could be hard to see the accumulation of coastal features, intrinsically linked over time, it is only possible to see the effects of what Gillian Clarke’s poem, Cantre’r Gwaelod’, describes as the ‘indifferent hunger of the sea’. Whilst it is possible to see the remains of the Shingle Ridge as it was and the smaller shingle ridge that runs the length of the back of the beach, it would seem to be a coastal location that is very much ‘coming into being’. It would be difficult to identify landmarks that provide clues to the trajectory of the coastline.

But perhaps, such locations should be seen as wild places, seascapes governed by natural forces, especially at a time of storms of increasing severity. Use of the approach of the Palimpsest, could provide tools to look through the local, forceful, intense action of Wind-Wave Storms. According to Stoneman, each erosion feature is distinct, but through its characteristics, relates either by its location or by its form to earlier examples. Use of the Palimpsest as a vehicle to see through erosion and sea state to create methods to interpret future marks of the storm.