“The winds of a thousand miles buffeted and blew, wind over tide, wave over beach, the whole force of accumulated energy finally crashing up against our cliff” Easternmost House, Juliet Blaxland.

This post uses a combination of mediums to discuss a period of high waves at the chosen locations of Lowestoft and Felixstowe on 31st March/1st April 2022. To begin, we have text that describes the image of storm waves hitting a cliff near Benacre in Suffolk, and above, a photo showing Thorpeness cliff a few days after the high wave period.

The juxtaposition of the two mediums isn’t intended to prove a causal link between the two, but is intended to discuss a category on CoastalMonitoring.org, which states Significant Wave Heights (SWHs) that reach a certain height in metres, are deemed to have met the Storm Alert Threshold. Waves that reach this height are predicted to have a return period of around four times a year and are of interest because they have the potential to move significant amounts of beach material. At Lowestoft the Storm Alert Threshold SWH is 3.11 metres and at Felixstowe, it is 1.94 metres.

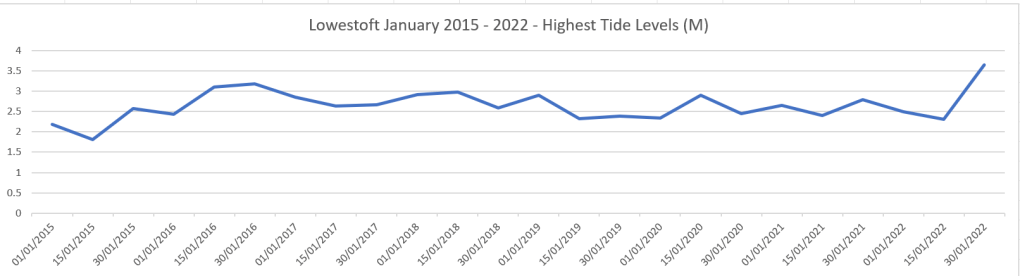

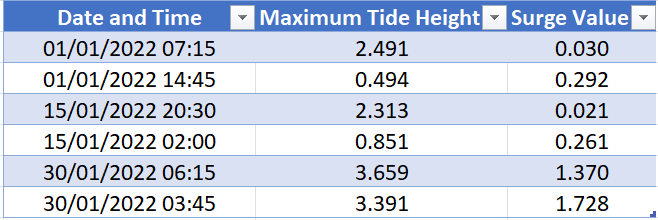

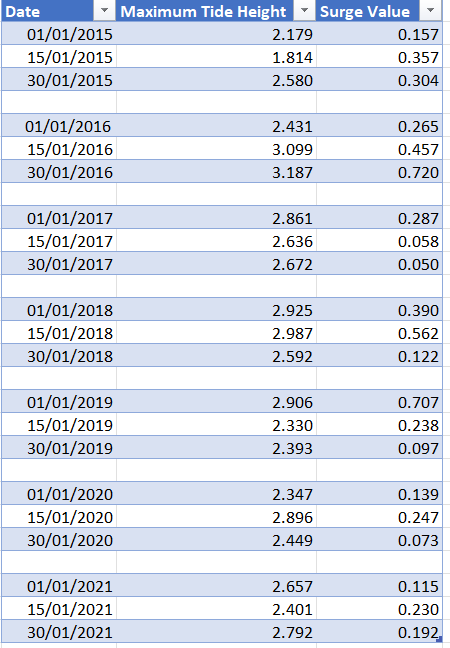

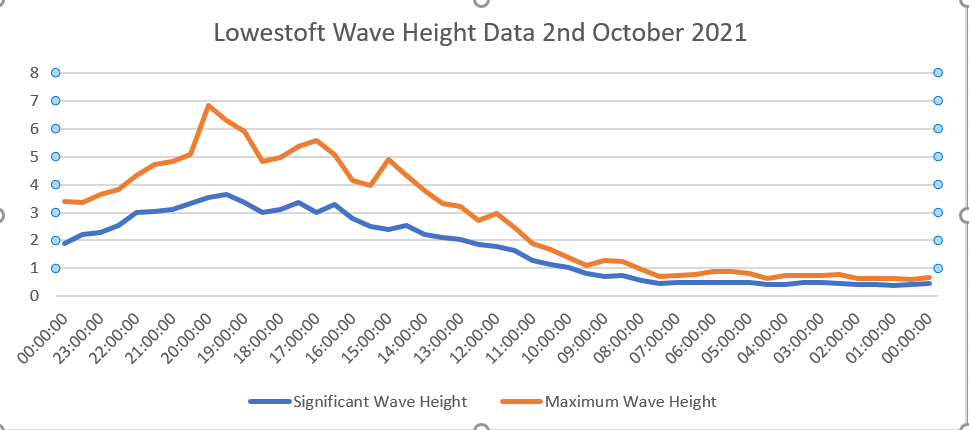

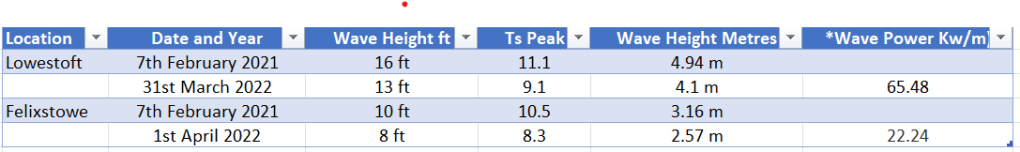

Another useful mechanism is to analyse wave height data. The source of all the data in this post is coastalmonitoring.org and the data is obtained from a Datawell Directional WaveRider Mk III buoy, owned by the Environment Agency. At Lowestoft the buoy was first deployed on 20th April 2016, and at Felixstowe, the buoy was deployed on 4th September 2012. For an explanation of the measure of Significant Wave Height, a post on this blog High Waves in October, provides more detailed information.

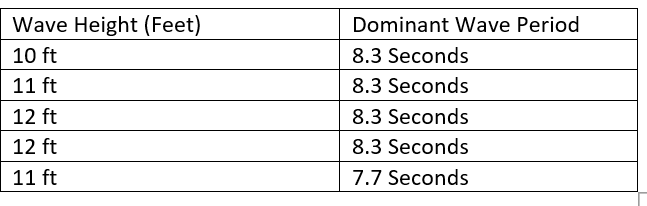

On the 31st of March and 1st April, the highest SWH for 2022 was recorded. As a comparison, the table below compares figures at Lowestoft and Felixstowe for 2021 and 2022.

The chart shows the highest Significant Wave Height in feet and metres. This enables a comparison with height in feet and the Ts Peak, which refers to the wave period where the highest wave energy is centred. It is believed when height in feet roughly matches Ts Peak, this indicates storm conditions. The figures for 31st March 2022 at Lowestoft, are more closely aligned, than those for 2021, but of most interest, are the figures for Felixstowe in 2021 and 2022, which pretty much match each other for height in feet and Ts Peak figure. The figures for wave height in metres, allow for a comparison with Wave Power, which is a measure added in 2022. Wave Power refers to the rate of transfer of energy through each metre of wave front.

This discussion intended use several mediums to consider the high wave period at the end of March/beginning of April. To add physical visualisation to this consideration, the photo at the top of this post, taken at Thorpeness beach, seems to show that the cliff has been gouged out with more trees lost over the cliff. Additionally, the East Anglian Daily Times describes how at Felixstowe, 25 beach huts were picked up by the sea and smashed together on the sea front on 1st April 2022.

The news report attributes high tides to the damage at the sea front, however, in this case, factors described later on in the article, namely strong north-easterly winds, were the main contributor to the coastal damage at the end of March/beginning of April. Interestingly, North-easterly winds are known to scour beaches, and observers of beaches around Sizewell and Covehithe who have experienced a loss of sand and shingle in recent months, might note that the East Anglian Times article, describes how up to 5 inches of sand and shingle were deposited on the sea front at Felixstowe.

The high wave episode discussed in this post occurred in a period in 2022 of exceptionally high tides and waves which have had a serious impact on coasts and estuaries. Future posts will continue to use a combination of mediums to discuss the wind on the waves in Suffolk.